UN Convention on Biodiversity: “Biological diversity” means the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.

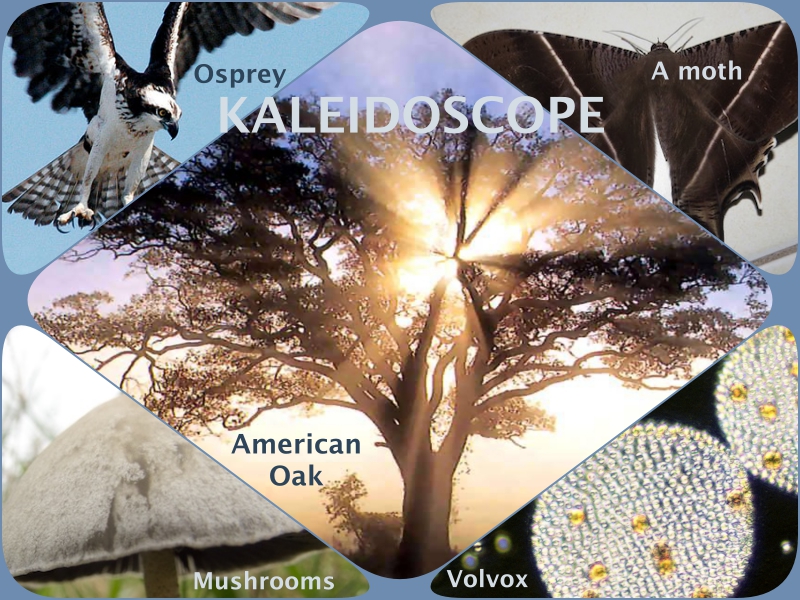

Since these pages are devoted to singing the praise of Biodiversity, it should be clear what we talk about here. Most people will instantly think of biodiversity as all species that exist. Most people will then think of birds, and mammals, and probably also trees, and flowers, and animals like bees, butterflies, fish and corals and the like. Organisms that are (relatively) easy to see or observe.

If so, then it should not be forgotten that creatures like mushrooms, worms, crabs, or for instance mosses and lichens belong to it as well. And not to forget tiny organisms like multicellular microscopic life like Volvox, and mono cellular life, such as diatoms (well, most of them are; some also come together to form colonies). And, although lots of people refer to them as “germs”, bacteria and viruses also belong to it. All these creatures make up the impressive gamut of species that make up biodiversity.

But …

The concept of Biodiversity doesn’t stop there. To understand that, it is worthwhile to look at the concept of species. When I studied biology, a sort practical definition that was accepted was that organisms belong to the same species if they can get fertile offspring. In other words, children should be able to procreate. This makes sense of course, since what make creatures what they are is determined by their genetic information. If that cannot be brought forward, then what makes something a species is not maintained. The process of evolution through which species come and go cannot work either. So the famous mule – a cross between a donkey and a horse – is not a valid species, because it is sterile.

However, that same concept of species becomes murky when for instance orchids are studied. Orchids are famous for their capacity to produce hybrids. As the website eMonocot writes on it’s orchid pages:

Many genera show a marked degree of interfertility both between their individual species and with species of other genera. This has given rise to innumerable artificial hybrids, both interspecific and intergeneric, which form the basis of a very important and extensive horticultural industry.

It has been said therefore that orchids, being a relatively new group of flowering plants, are still fully in the phase of generating species. But other groups have problems as well. Recently I came across two gibbon species, for instance, that illustrate that conundrum. One is called Nomascus siki, or Southern White-cheeked Gibbon. The other one isN. leucogenys, or Northern White-cheeked Gibbon. The IUCN Red List site webpage for the Southern White-cheeked Gibbon says:

This taxon is variously considered a subspecies of N. concolor, N. leucogenys and N. gabriellae (M. Richardson pers. comm.). This may not be a genuine species, but rather, a natural hybrid of N. leucogenys and N. gabriellae. According to Delacour (1951) and Groves (1972), this species may possibly interbreed with N. gabriellae in Saravane and Savannakhet, Lao.

Inter-species variation

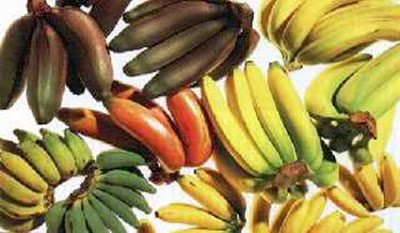

This consideration brings the idea of sub-species into the discussion. Within a species – regarded as a natural unit that separates one group of organisms from all other organisms – are sub-groups of organisms that share genetic information, are distinctly different from other subgroups, but yet it is possible to have fertile offspring produced by individuals from different subgroups. This is one way in which evolution works. It is also a way in which humanity has produced lots of food crops and livestock. All those different varieties of potatoes, beans, chickens, cows, horses, rice, manioc, tomatoes, bananas, corn or maize, and so on, are fine-tuned to the environment for which they were developed. But all those varieties can in principle interbreed.

This discussion isn’t so much about the concept of species, as it is to emphasise the role of genes for biodiversity. It is the package of genes and the variety that exist within individuals of the same species that make up biodiversity. So biodiversity includes species, and varieties, in order to capture the essential quality of the concept Biodiversity.

This brings us back to viruses. The question whether viruses are alive or not is irrelevant. Viruses contain genetic material and they change, evolve, constantly. For that reasons, they belong to biodiversity. Prions are wrongly shaped proteins and are not regarded as living organisms: they do not contain genetic material, and don’t have a cellular structure. They would therefore not be part of biological diversity. (Yet they are infectious! Read more here.)

Still not all …

All creatures live together in systems. Such systems are referred to as ecosystems. When I studied, the idea of ecosystem was a relative idea. A fresh water lake was considered an ecosystem, but the forest that contained such fresh water lake as well. Another school preferred more static definitions. A forest with lakes in it, would be considered a landscape for instance, and the forest as such an ecosystem, as would be the fresh water lake. Whatever conceptual approach is used for the term ecosystem, the basic idea is the same. Organisms do not live in isolation. They always live together in systems. Evolution is the process that describes how species are formed and how they are changed and give birth to other species. This works under pressure of the environment of such species. Pressure comes from non-living elements, such as soil chemistry or physical properties of soil, water availability and so on. It some also from other organisms that live within that system. Birds of prey hunting small birds or insects. Caterpillars eating the leaves of host plants. And so on. Species and varieties develop because of the systems they live in. Ecosystems belong therefore also to the concept of Biodiversity.

Convention on Biodiversity

Most countries have agreed to preserve biological diversity via ratification of the United Nations Convention on Biodiversity (CBD). In this convention are a number objectives and measures to actively work towards sustainable development and preserve this diversity. The text of the convention (Convention on Biological Diversity. IUCN, June 5, 1992.) uses the definition of biological diversity quoted above. On it’s website it says it a bit more elaborate, incorporating the elements discussed above:

Biological diversity – or biodiversity – is the term given to the variety of life on Earth and the natural patterns it forms. The biodiversity we see today is the fruit of billions of years of evolution, shaped by natural processes and, increasingly, by the influence of humans. It forms the web of life of which we are an integral part and upon which we so fully depend.

This diversity is often understood in terms of the wide variety of plants, animals and microorganisms. So far, about 1.75 million species have been identified, mostly small creatures such as insects. Scientists reckon that there are actually about 13 million species, though estimates range from three to 100 million.

Biodiversity also includes genetic differences within each species – for example, between varieties of crops and breeds of livestock. Chromosomes, genes, and DNA-the building blocks of life-determine the uniqueness of each individual and each species.

Yet another aspect of biodiversity is the variety of ecosystems such as those that occur in deserts, forests, wetlands, mountains, lakes, rivers, and agricultural landscapes. In each ecosystem, living creatures, including humans, form a community, interacting with one another and with the air, water, and soil around them.

It is the combination of life forms and their interactions with each other and with the rest of the environment that has made Earth a uniquely habitable place for humans. Biodiversity provides a large number of goods and services that sustain our lives.

Species coming and going – but now they are going too fast ….

And climate change is the dangerous process that we now embark on that will heavily impact on this diversity. The myriad of relations between living organisms and therefore between living organisms and non-living elements like soil are going to be changed in unforeseeable directions and magnitudes. After centuries of work, various examples around the world show that often it is not yet completely understood how ecosystems work precisely. Taking out so many elements in rapid succession out of these systems by altering the physical conditions through climate change is a very dangerous experiment. It will make life for people very difficult for decades, if not centuries to come, by causing huge changes in the conditions that we are to live in.